Slacking Noise

Notes on Richard Linklater's published 'screenplay' of SLACKER or: How I Learned to Make Movies by Reading a Book. Plus, Matt finds something cool at the Rose Bowl.

Richard Linklater’s Slacker was a core piece of physical media for me (Dave) when I picked up the Criterion DVD in college. It was not only inspiring proof that true indie filmmaking was still possible, but it also possessed a heady, funny, & philosophical style that I badly wanted to emulate. So, after graduation, as I began teaching myself how to write movies in LA, I did the obvious thing and tracked down the scripts for all of my favorite movies.

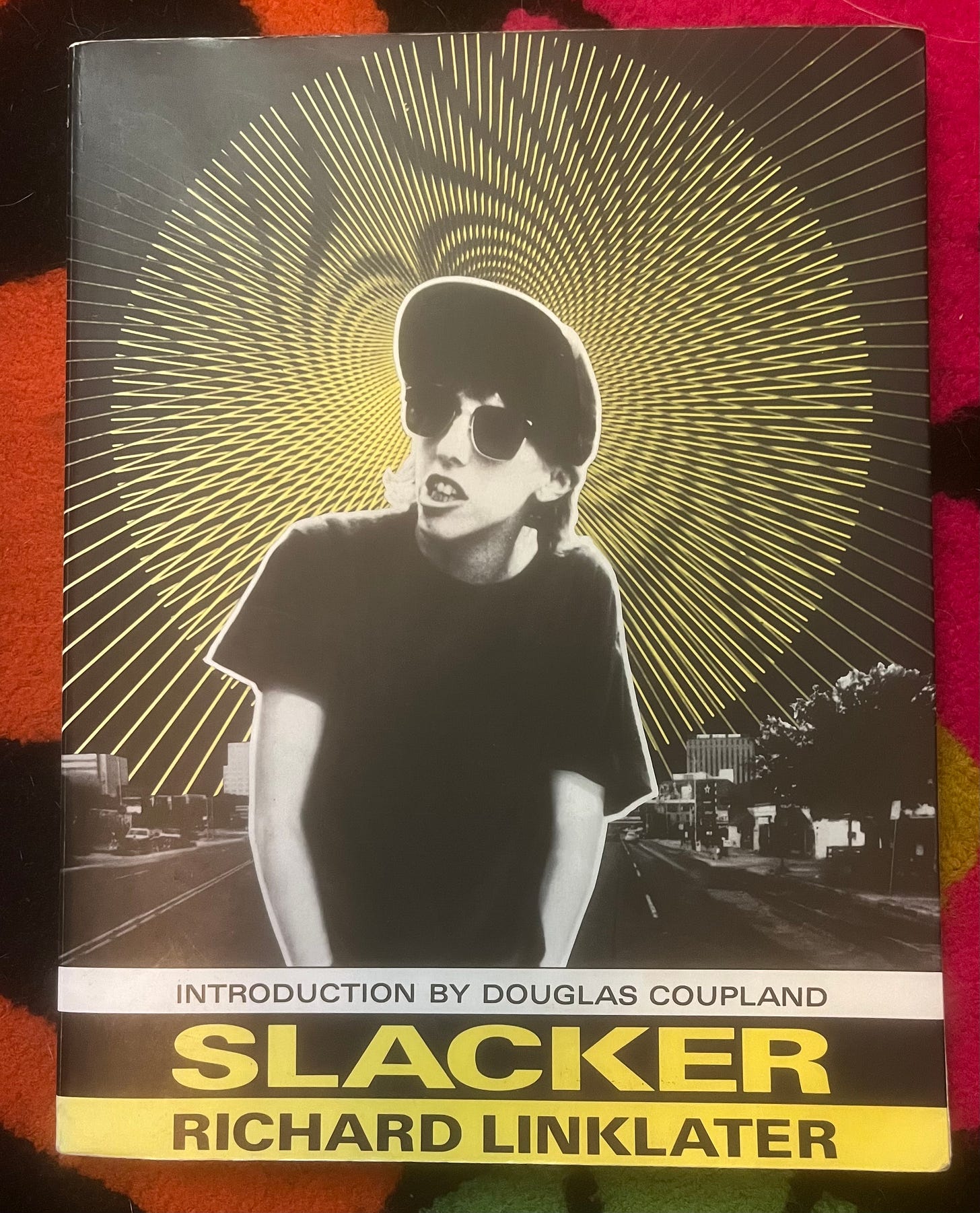

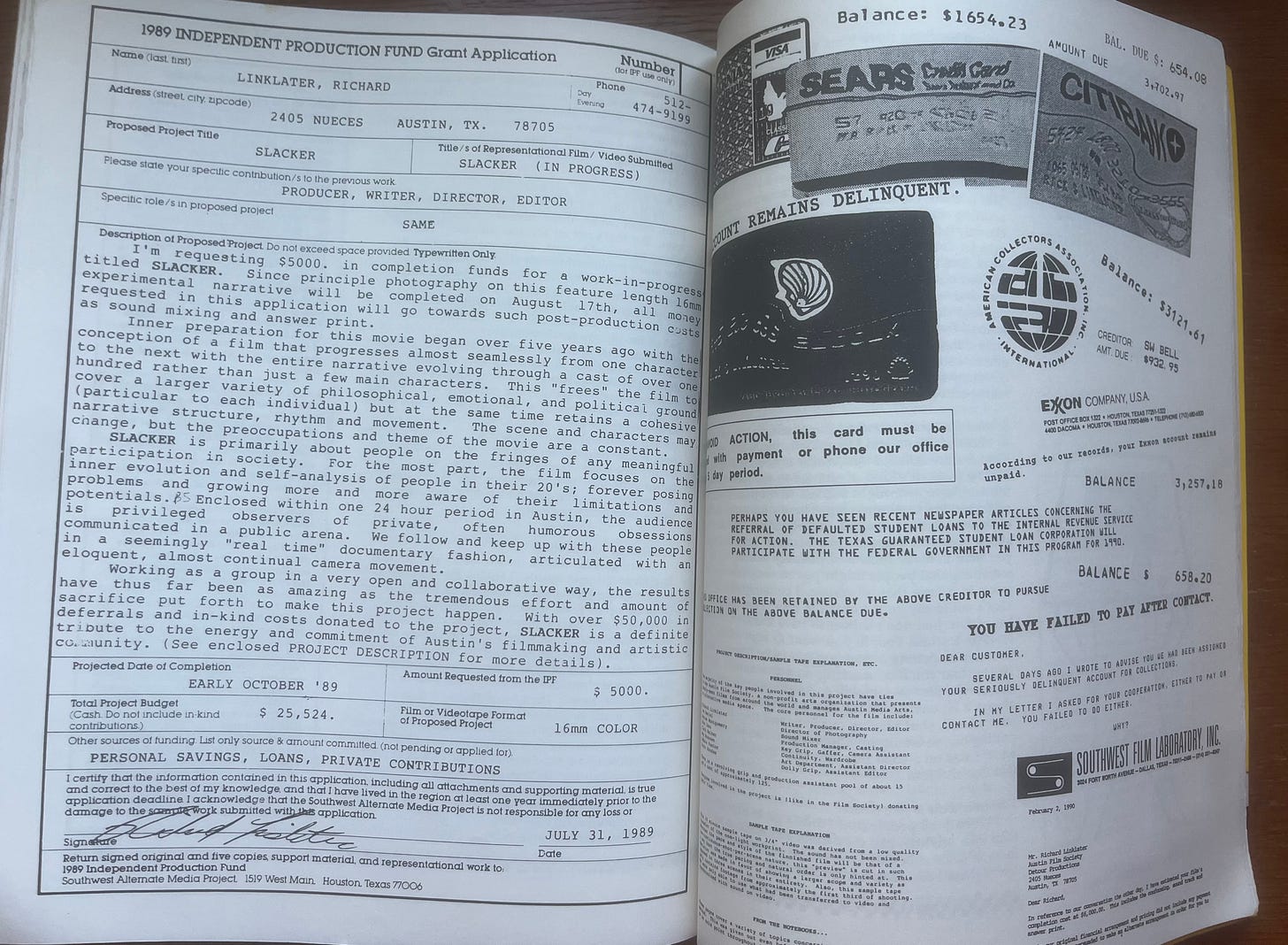

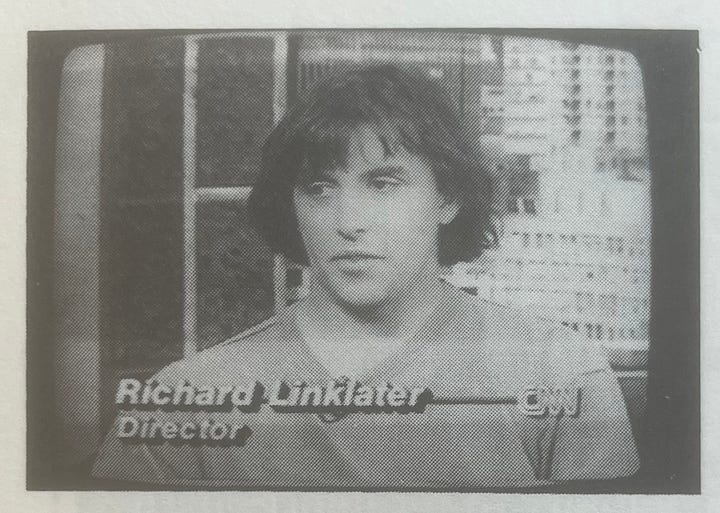

Some were available online but most were only available in book form — which led me to this 1992 St. Martin’s Press publication of the Slacker screenplay. At the time, this kinda seemed like a misnomer to me since I knew from a film class that the movie was proudly improvised and largely “unscripted.” But I bought the book anyway, and it turned out to be so much better than just another published script. This was more like a Living Document For How To Make A Movie — containing not only two versions of the “script,” but also essays about the process by Linklater, snippets from his production diaries, funny character bios for each actor, xeroxed credit card bills for film stock, fliers from Austin rock shows, hand-drawn conspiracy artwork, and even a brief introduction from the actual guy who coined the term “Gen X.” Of all the books I have on movies, this might be my favorite.

With SXSW in full swing, we thought we’d honor Richard (“Rich”?) Linklater — sui generis of indie filmmaking, longtime champion of Texas cinema, and esteemed author of this hidden gem that every aspiring filmmaker or film fan should read — by highlighting some of our favorite parts.

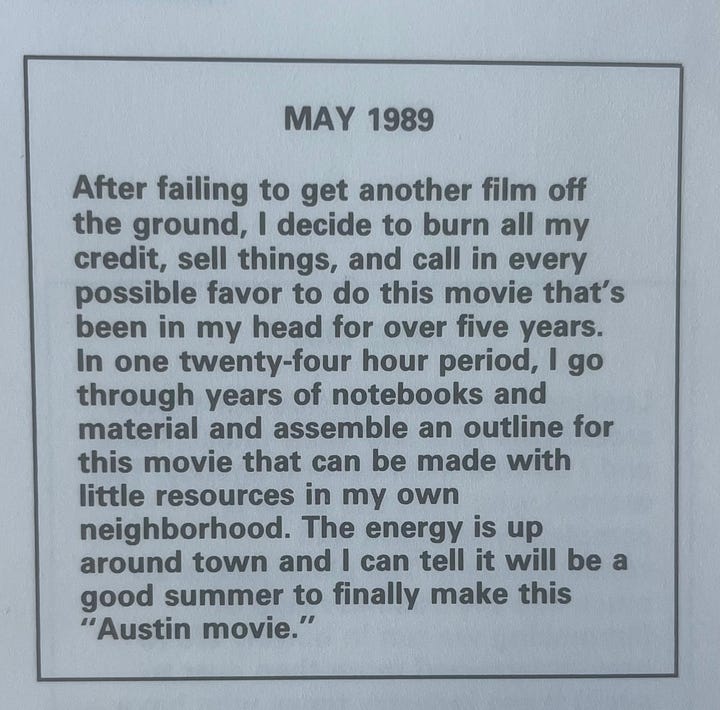

Peppered throughout the book are excerpts from a diary Linklater was keeping at the time, starting from before he’d even written the script (or rough outline) for what would eventually become Slacker and continuing on through the release of the film. He offers brutal insights into the difficulties of the independent filmmaking process as well as some inspiring anecdotes like the one above, where we can see an early glimmer of his uncompromising and visionary approach to making this film.

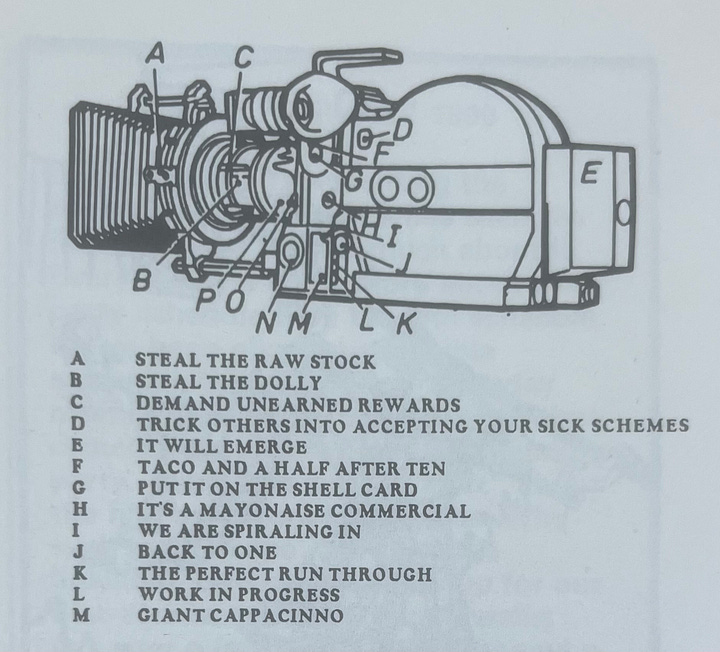

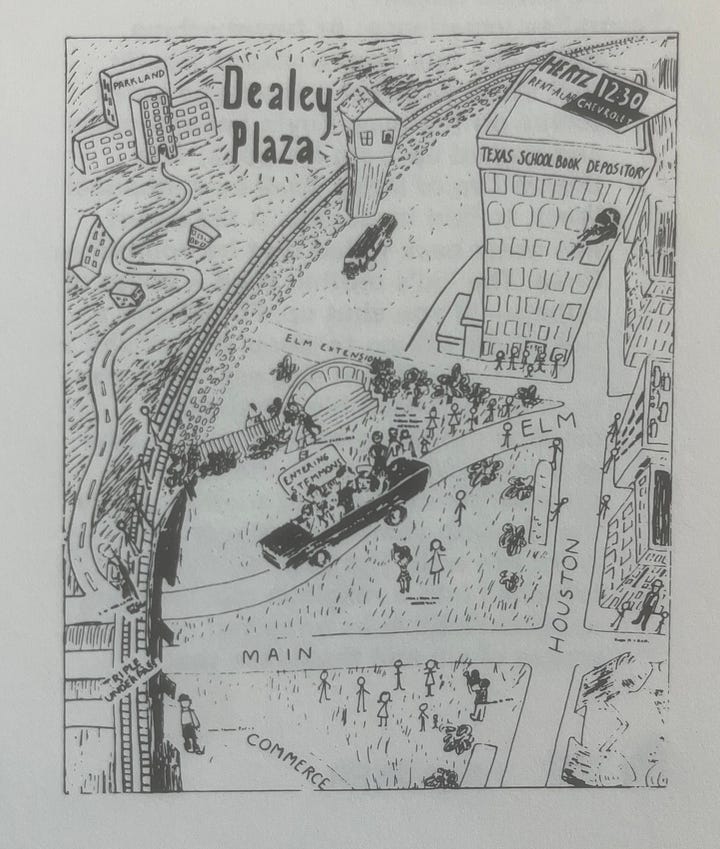

Many pages of the book are decorated with funky sketches and random hand-drawn graphics, ranging from in-joke camera diagrams to JFK conspiracy maps:

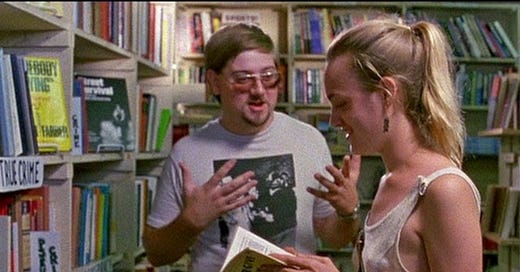

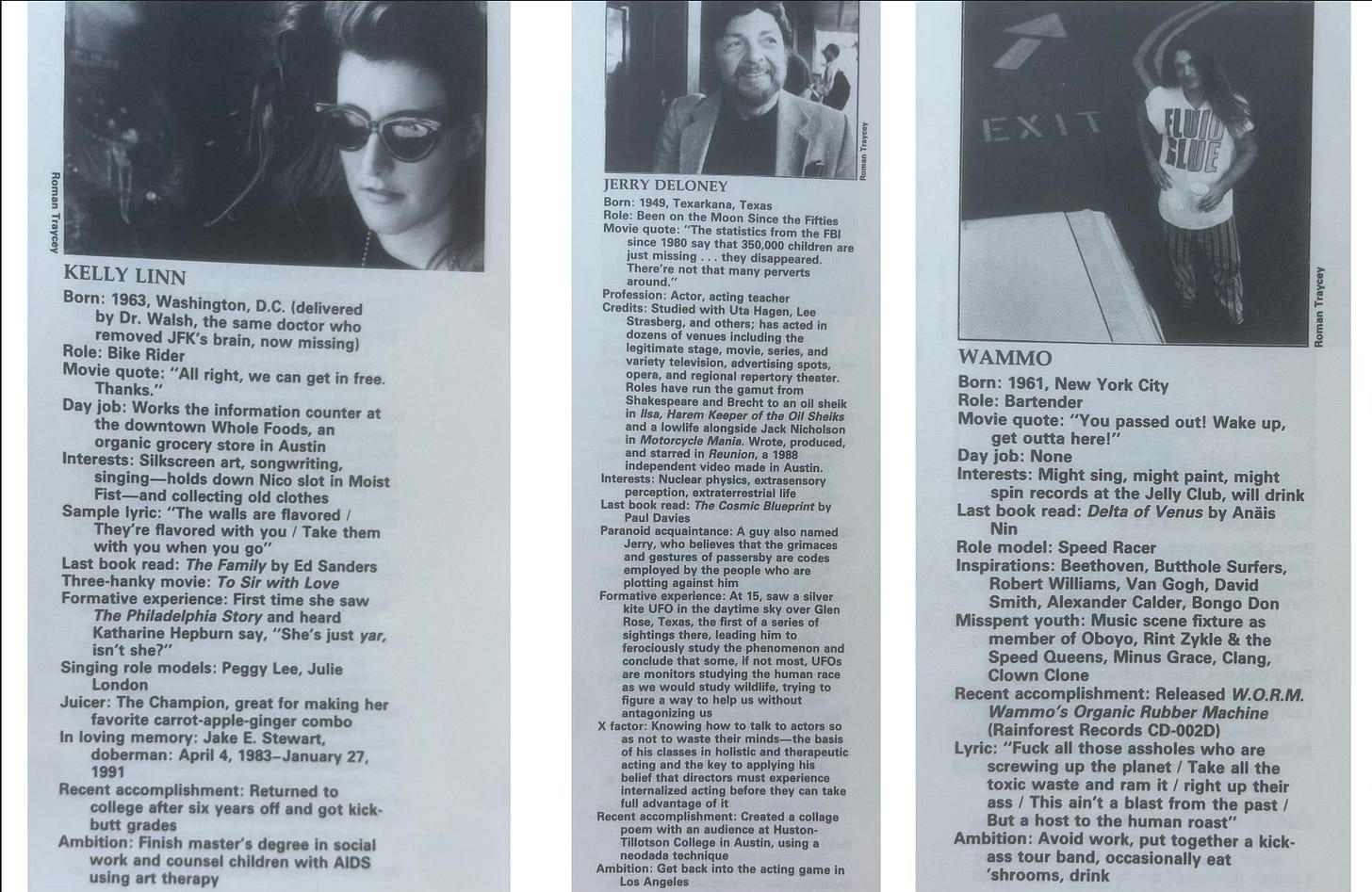

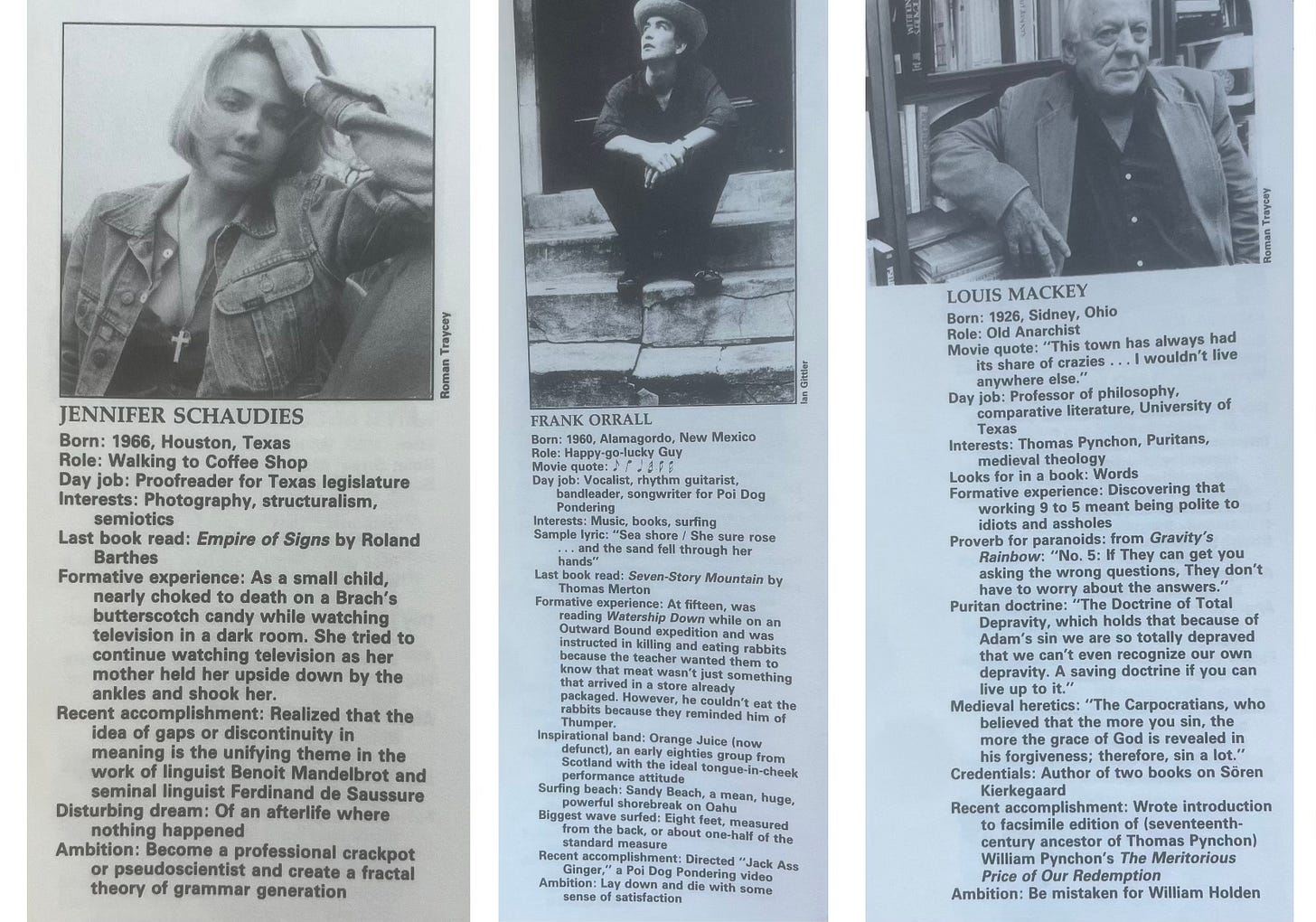

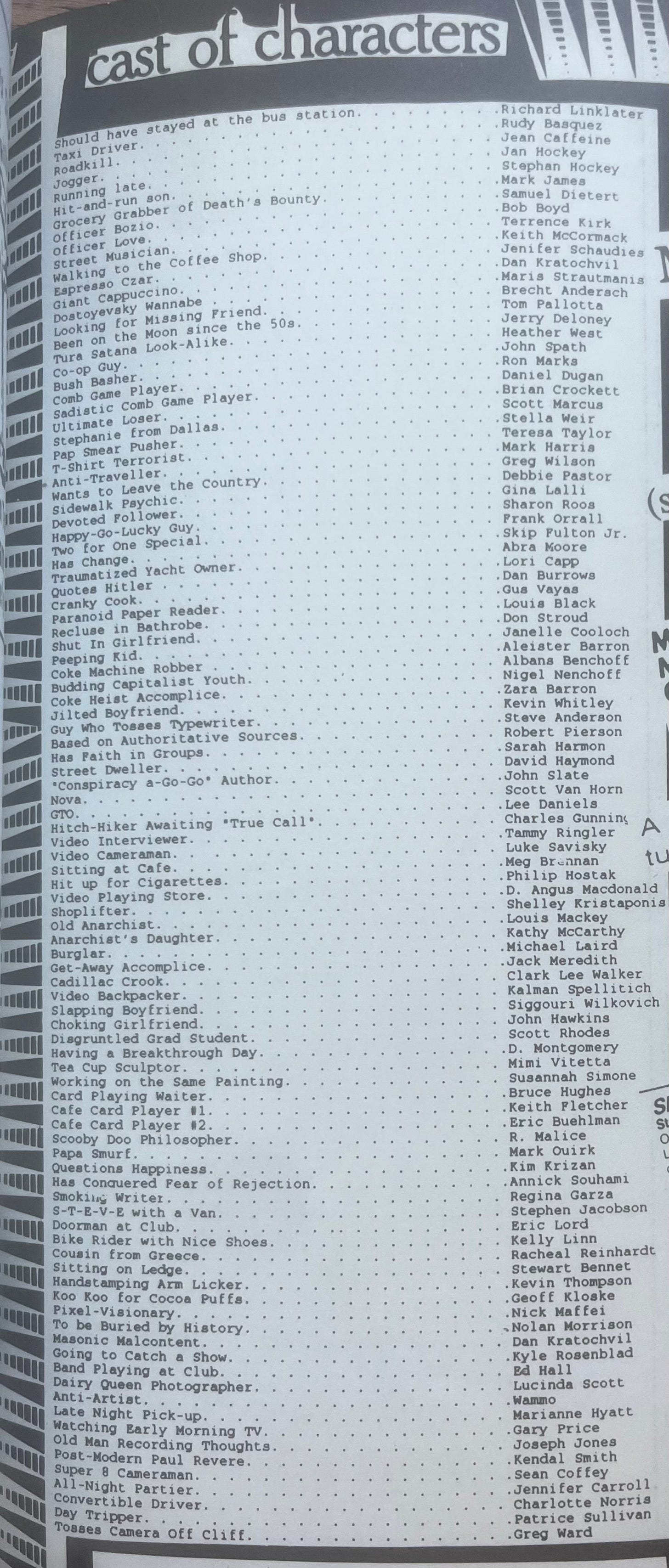

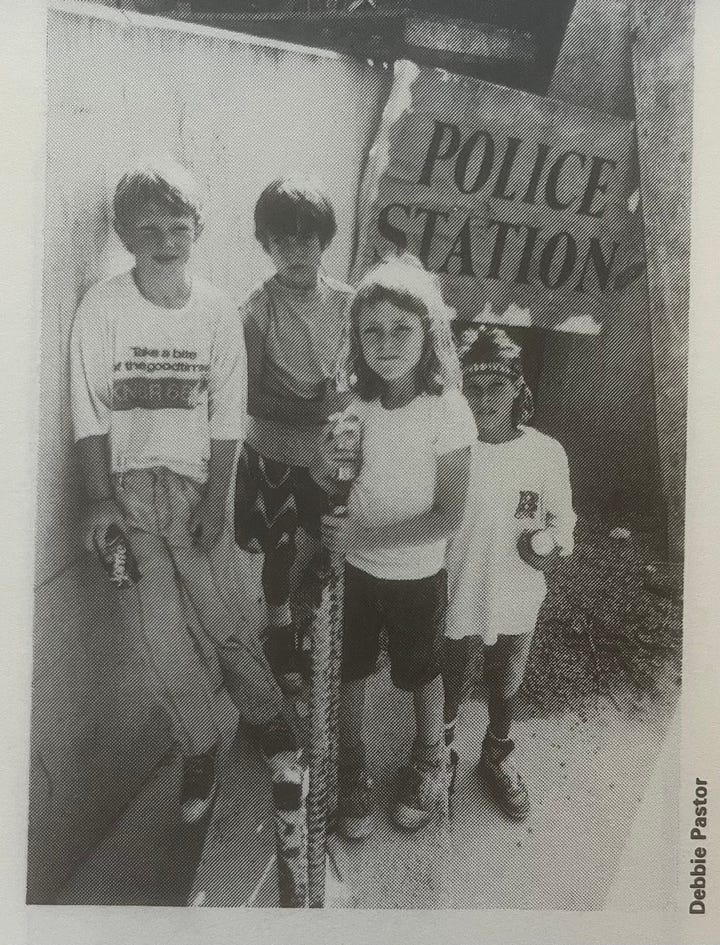

If you’ve never seen Slacker, it is — in both form and theme — a movie about people. Structurally, the entire story is an episodic odyssey from one person to the next, with no “main character” or “antagonist” or anything remotely close to it, and a cast almost entirely composed of non-actors. In his introduction, Douglas Coupland described Linklater’s cast as “…dreamers on the edge, characters out of key, in and out of love, drifting, slightly twisted, still willing to listen — childlike and full of wonder with their world — people I would like to consider my friends.” Every one of the ‘actors’ featured in the film is given their own 1/3-page sidebar and they are incredible, overflowing with personality and hot cultural takes circa ‘92:

My guy Wammo in general deserves a special shout-out. Every answer is better than the one before. I just hope wherever he is now, he’s not lifting a finger on anything work-related, still “might paint,” and is eating more than the occasional fungus.

As expected, these were very literary folks. The authors namechecked here — Barthes, Merton, Pynchon — happen to be three of my personal top dawgs. Follow the advice of these freaks and read everything you can by those 3 writers.

Also, since Thomas Pynchon has never made a movie and can’t claim the title for himself, I think Slacker wins for “Best Character Names” in any movie:

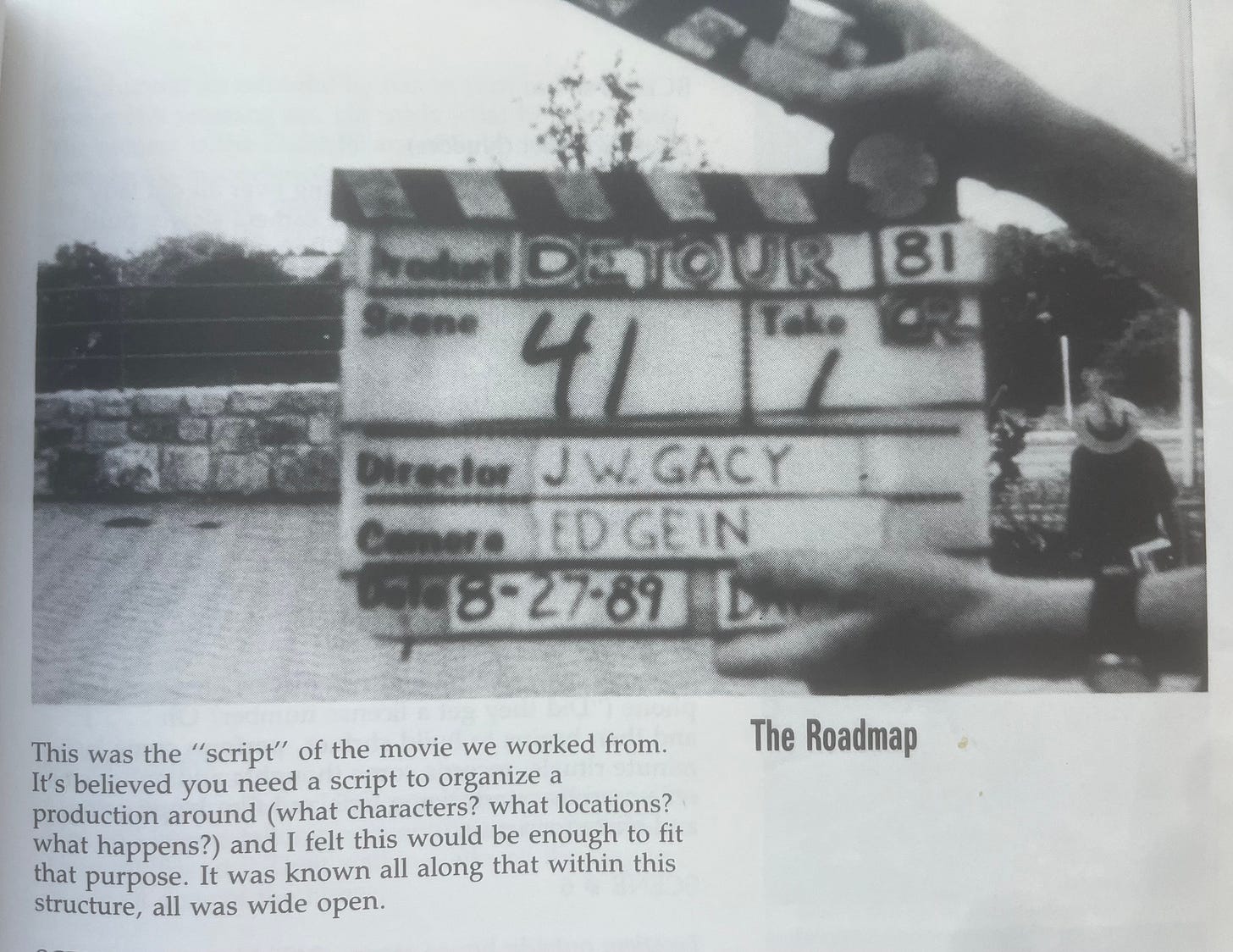

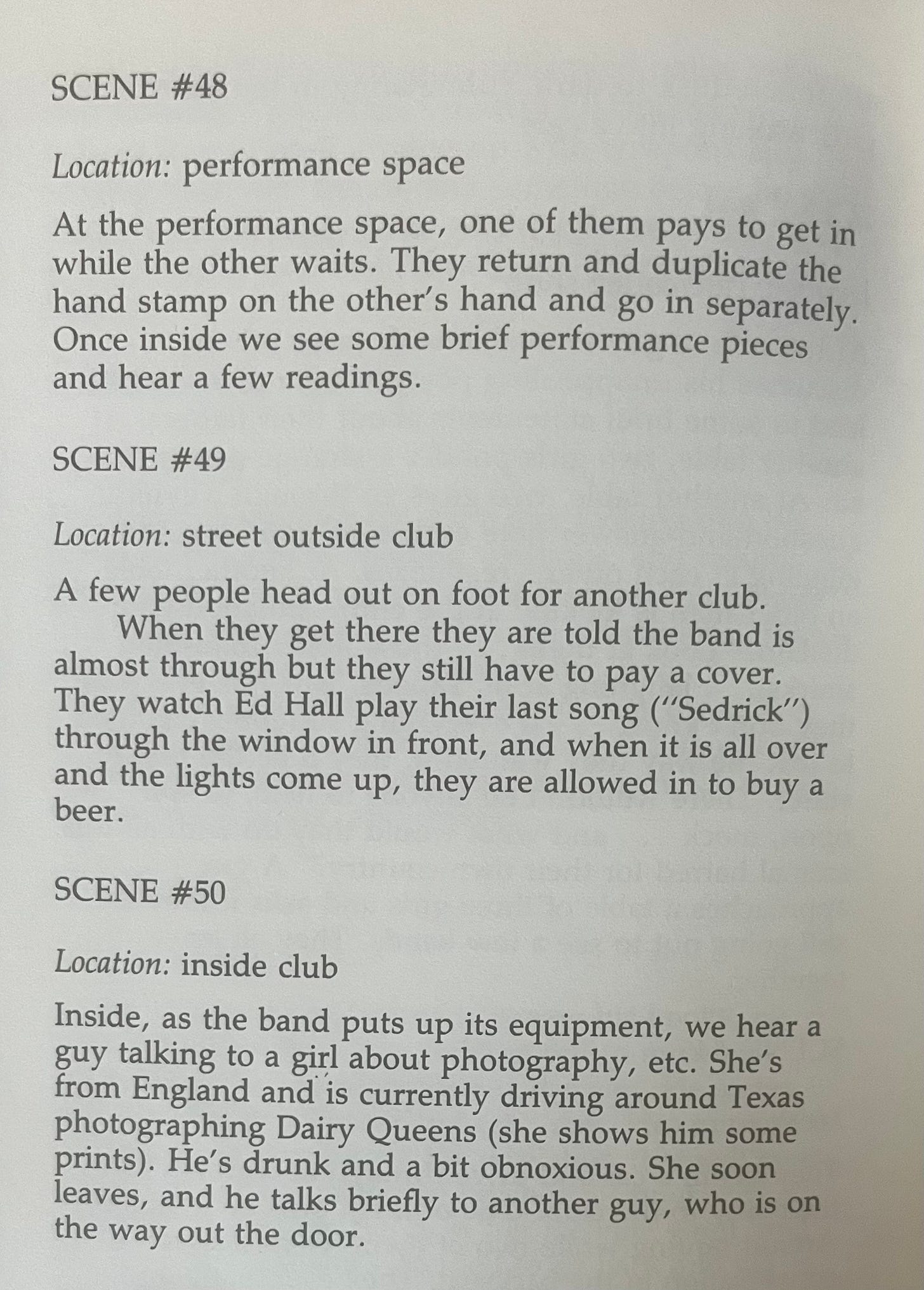

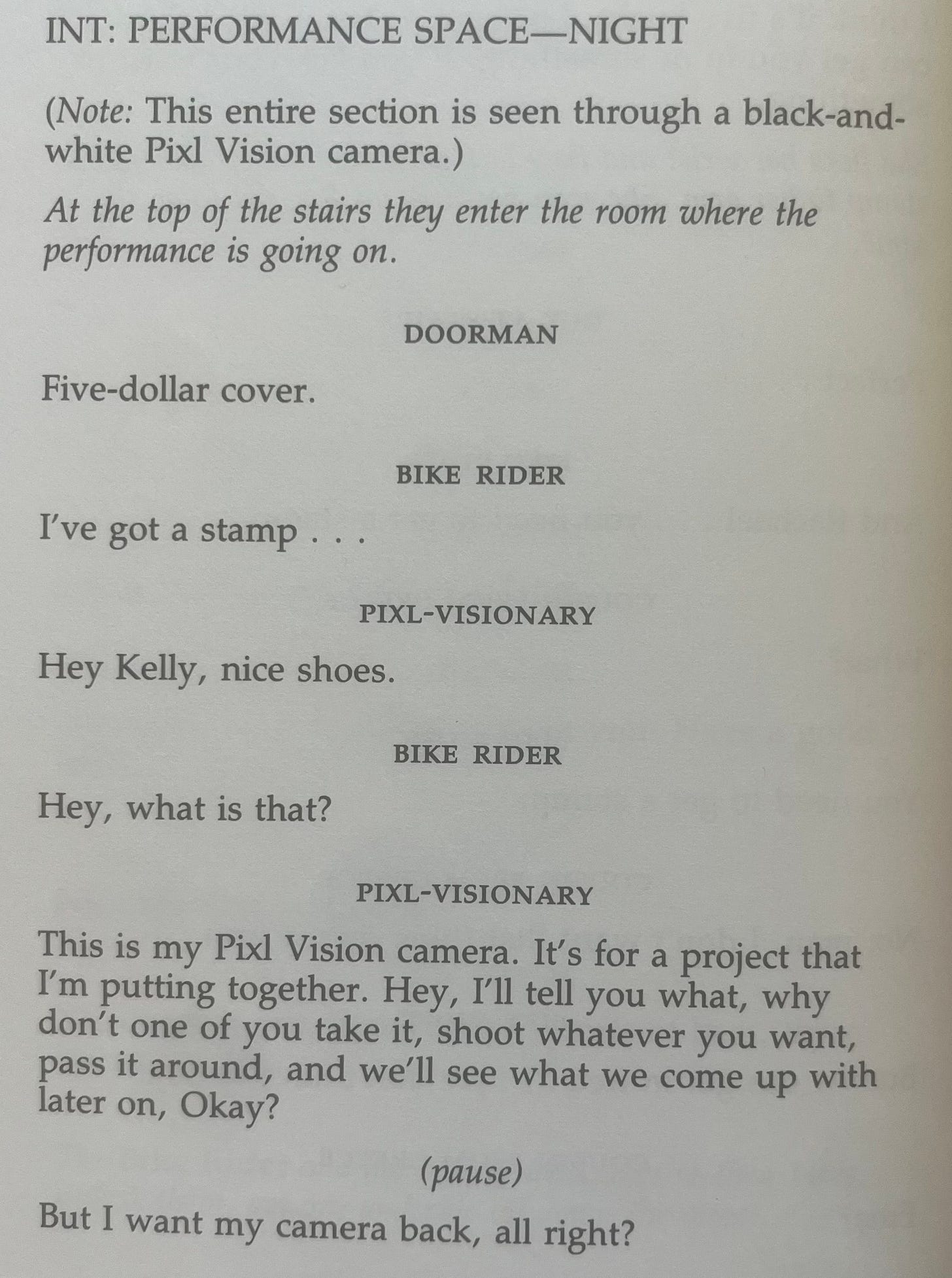

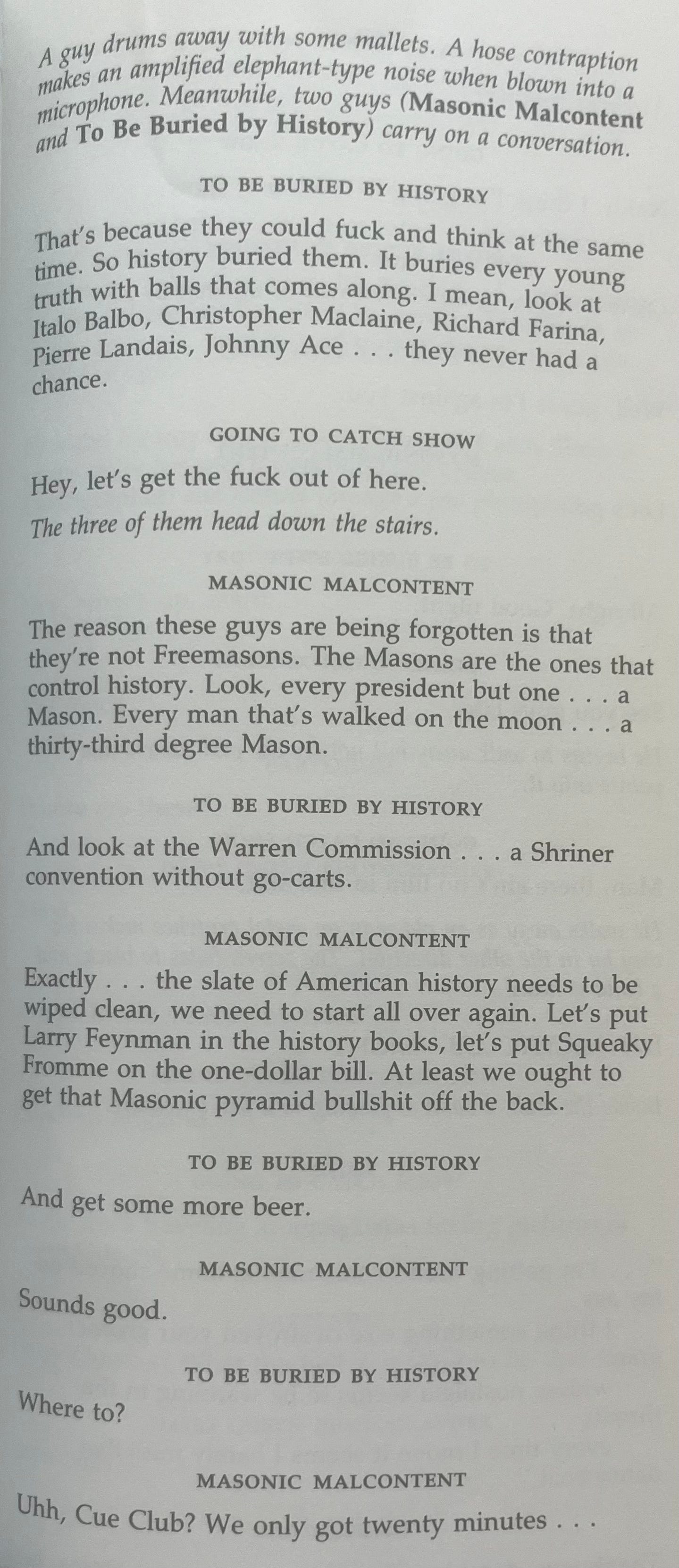

The next section is “The Roadmap,” which is as close to a shooting script for Slacker that exists. In no way does it resemble what a screenplay should look like. In fact, it’s kind of a case against having formal screenplays — the kind I write for a living — at all. Is this post just a massive self-own? Read on to find out!

The scenes here are as spare as you’d expect, but they also contain a level of specificity (i.e. highbrow name-drops and cultural references) that give added depth even in the improvised form. What at first seems like a shaggy outline is actually an extremely precise guide for how the eventual scene plays out.

In the following section, Linklater transcribes the finished movie and formats it the same way Trad Screenwriting Professionals like I do, and it’s fascinating to see how the film evolved throughout production:

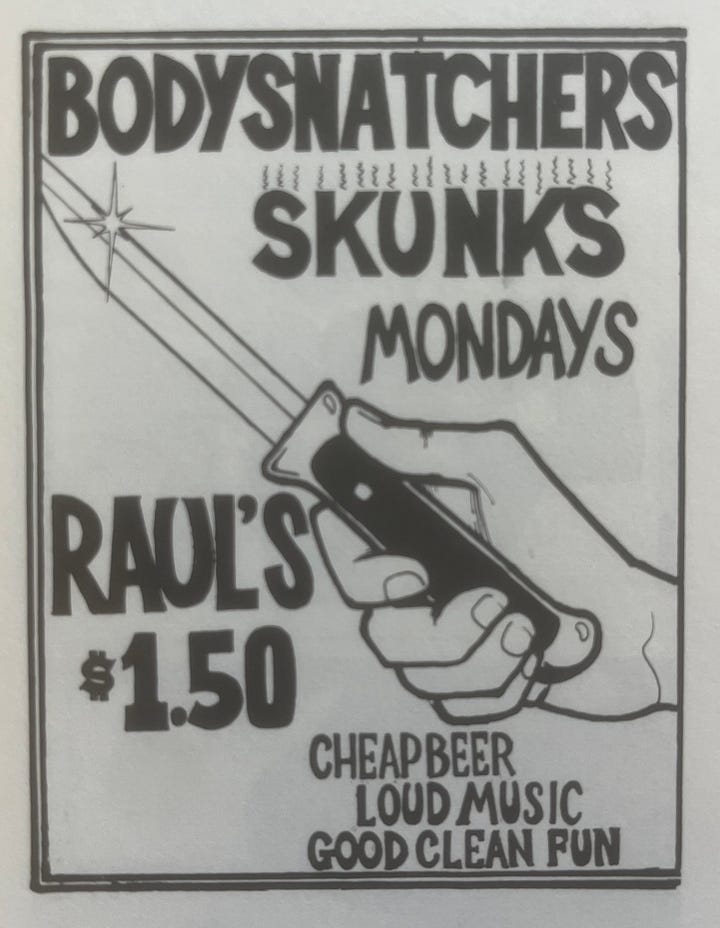

In addition to drawings, the book includes all sorts of random stuff like vibey old photos taken around Austin and bad-ass concert fliers with glittering switchblades. What a time to be alive!

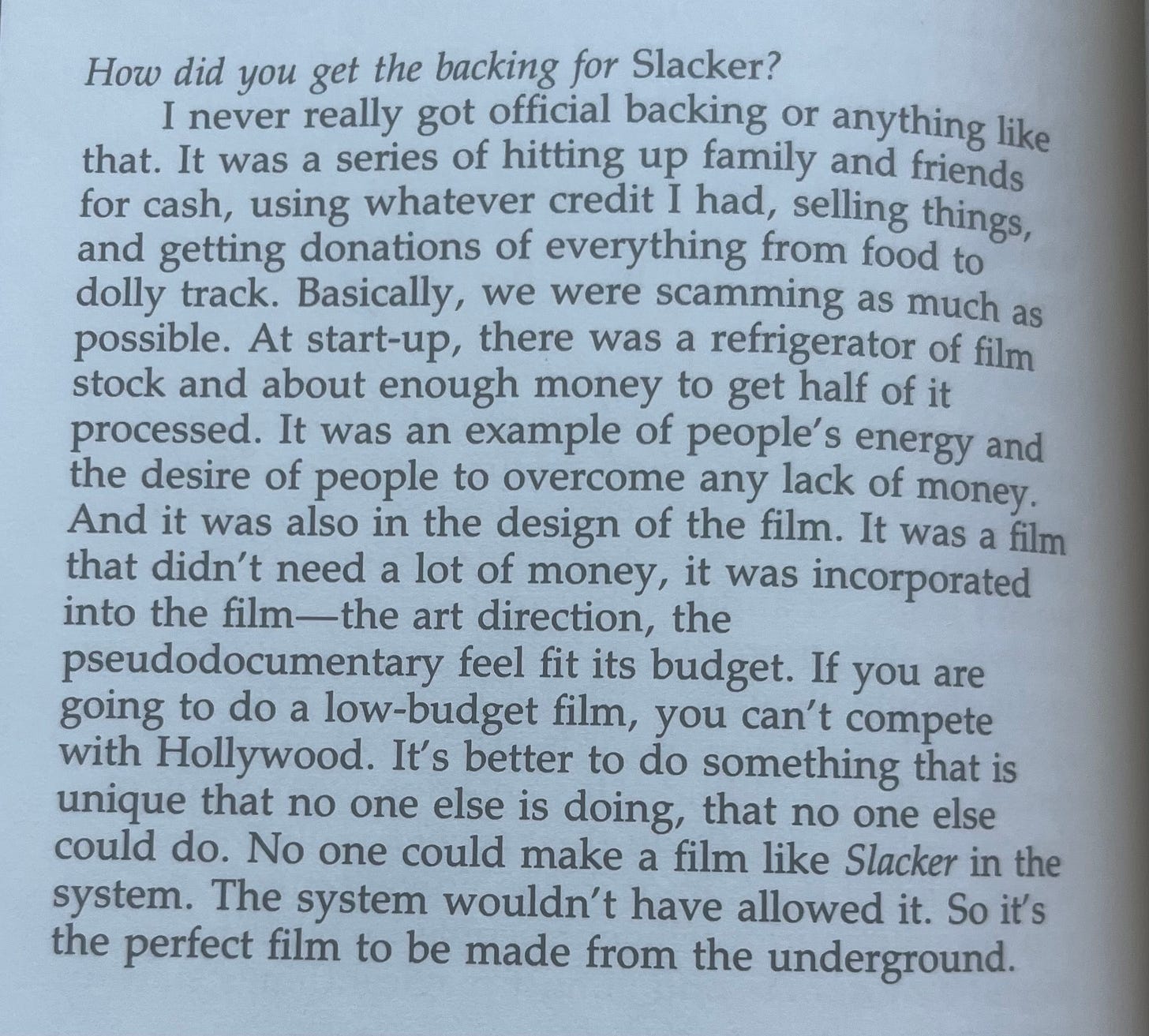

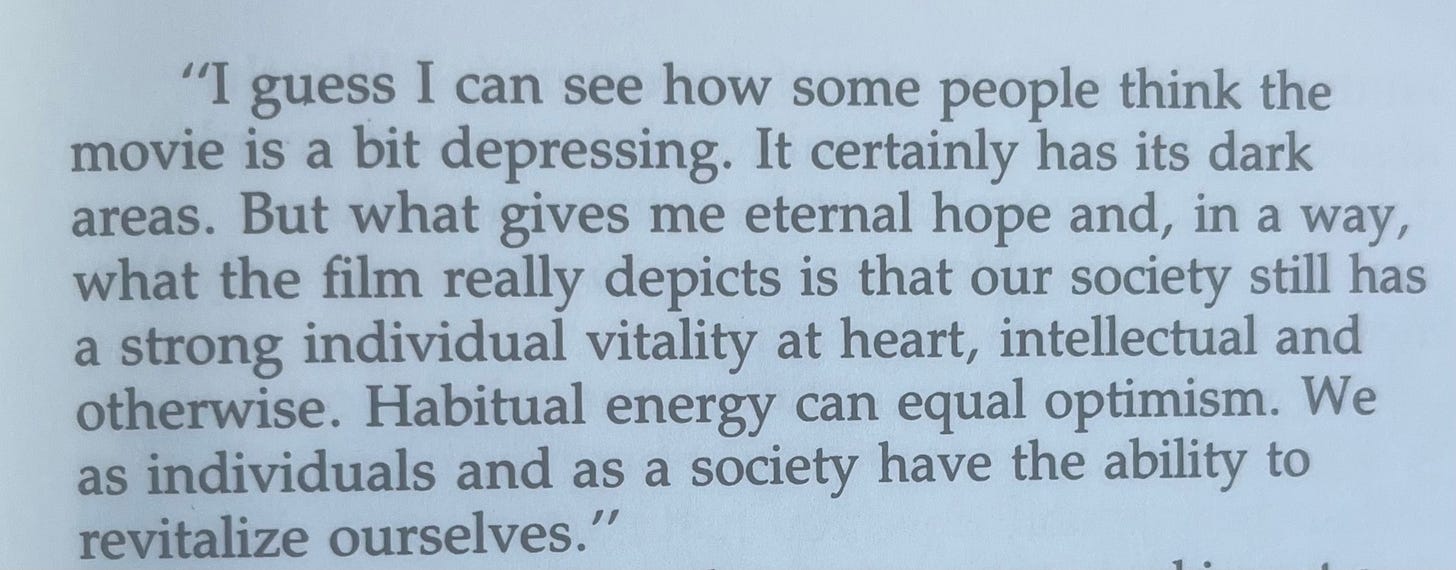

In the final section, Linklater gives an illuminating interview where he reflects on the entire process and it’s laced with the hallmark philosophical musings, open-heartedness, and devotion to the craft we’ve come to expect of the man:

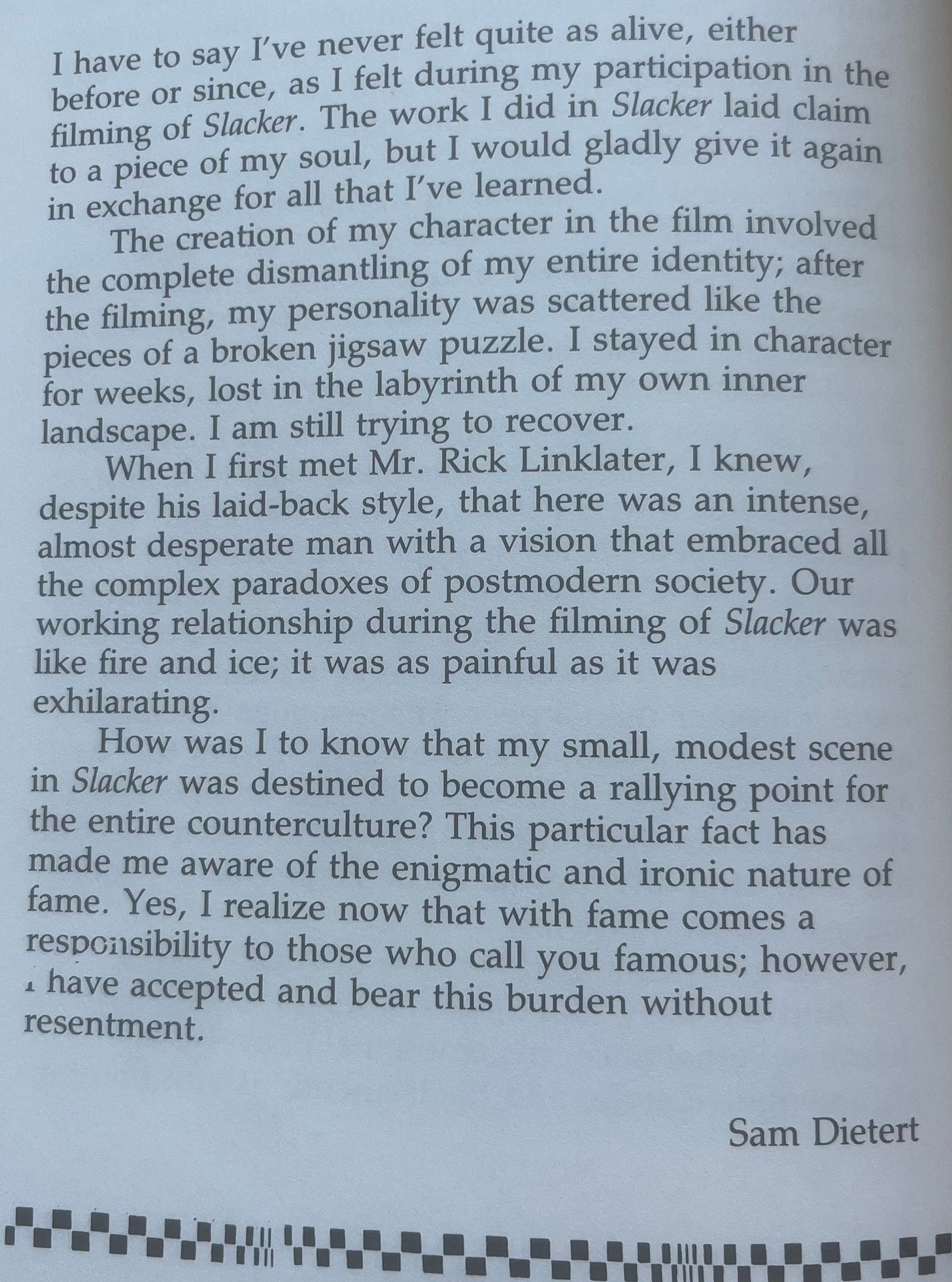

This is followed by various members of the cast and crew talking about how much the experience of making Slacker meant to them. This one in particular really got me:

Someday (hopefully a long time from now) my tombstone will read: “Despite his laid-back style, here is an intense almost desperate man with a vision that embraced all the complex paradoxes of postmodern society.”

In the final pages, Linklater includes a cheeky accounting of all the financial woes he faced while making the movie and the receipts to prove it:

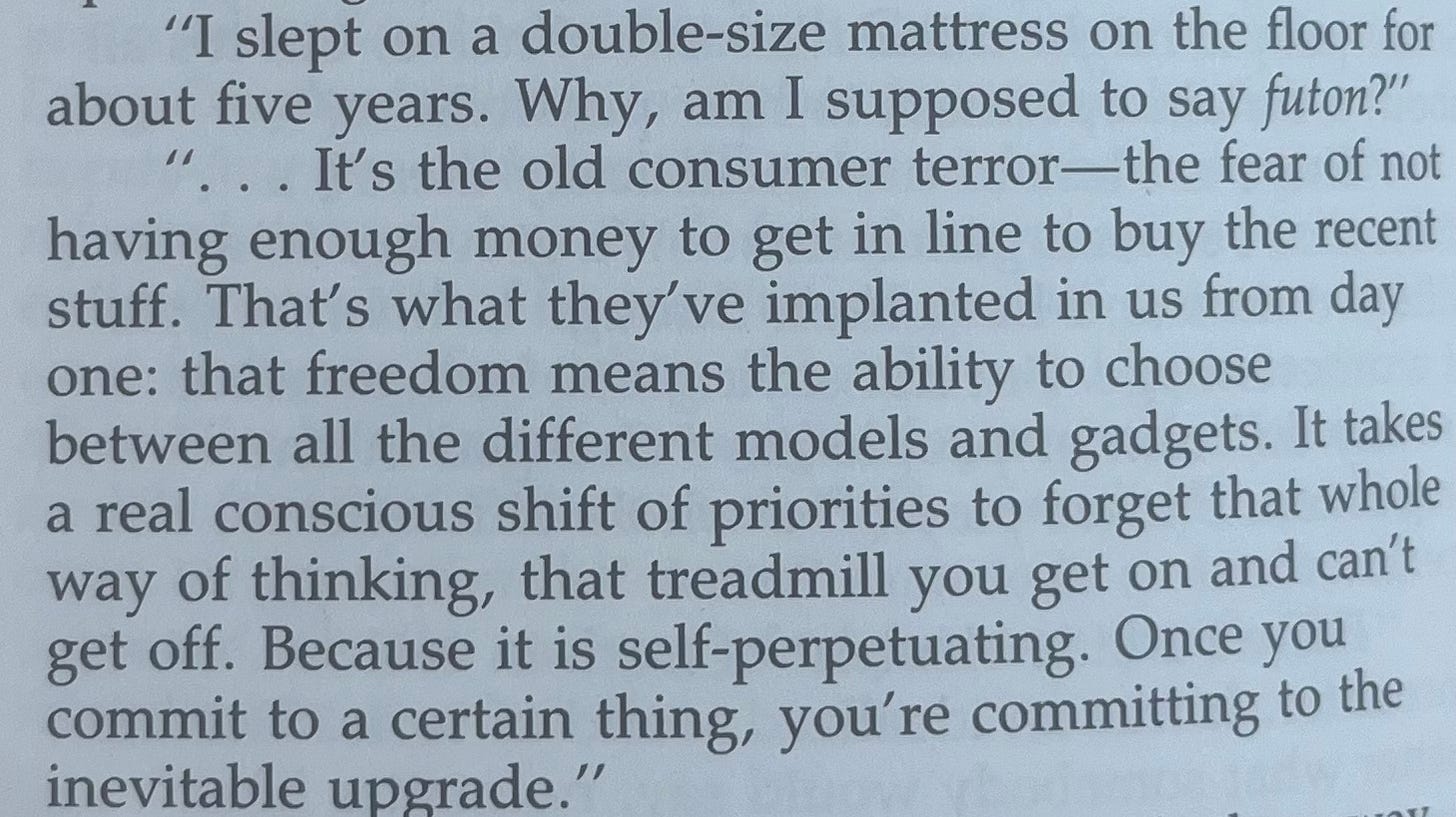

And just because Richard Linklater is one of the wisest cinematic sages we got — I copied down almost the entire book into separated quotes in my notes app — here’s a final excerpt that feels strangely resonant to what we’re facing today. Only the treadmill’s moving faster than he could have ever imagined, so we should probably take these words to heart:

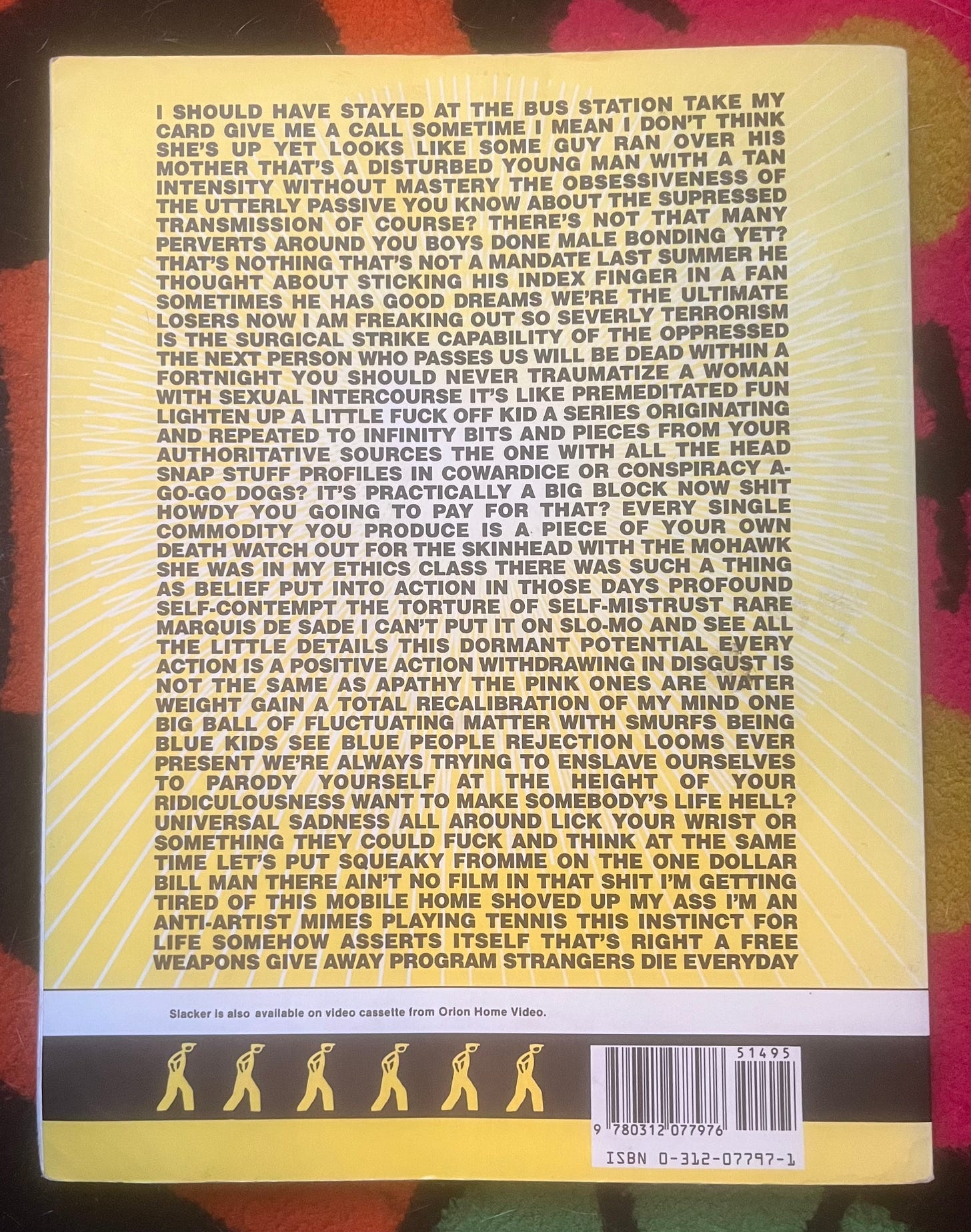

The back cover features a small portion of the legendary monologue delivered by the very first Slacker in the movie, aka Richard Linklater himself. The writing in this scene is brilliant — couched between the umms and likes of a wide-eyed Gen X twentysomething’s ramblings is a deeply thought-provoking meditation on Choice that braids together all sorts of philosophical ideas — from Schrödinger's cat to quantum mechanics to Nietzsche's"the circle of time.” I also realize I’m talking about the opening of the film at the end of this post, which is exactly the kind of circular irony Linklater himself would appreciate.

Thank you Richard Linklater for inspiring me and spawning a lot of really bad imitators (also me). You can purchase a used copy of the book here and the film here.

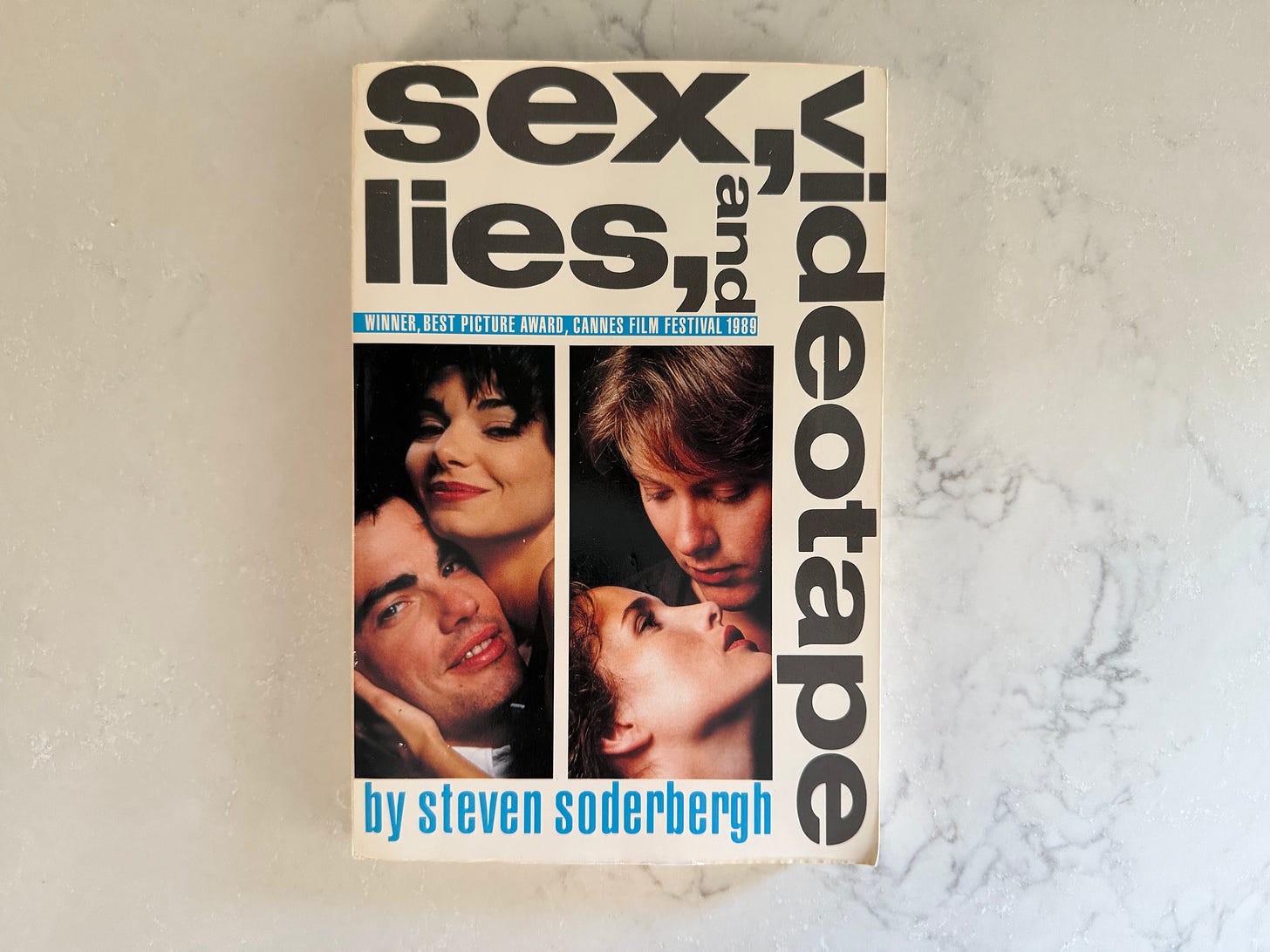

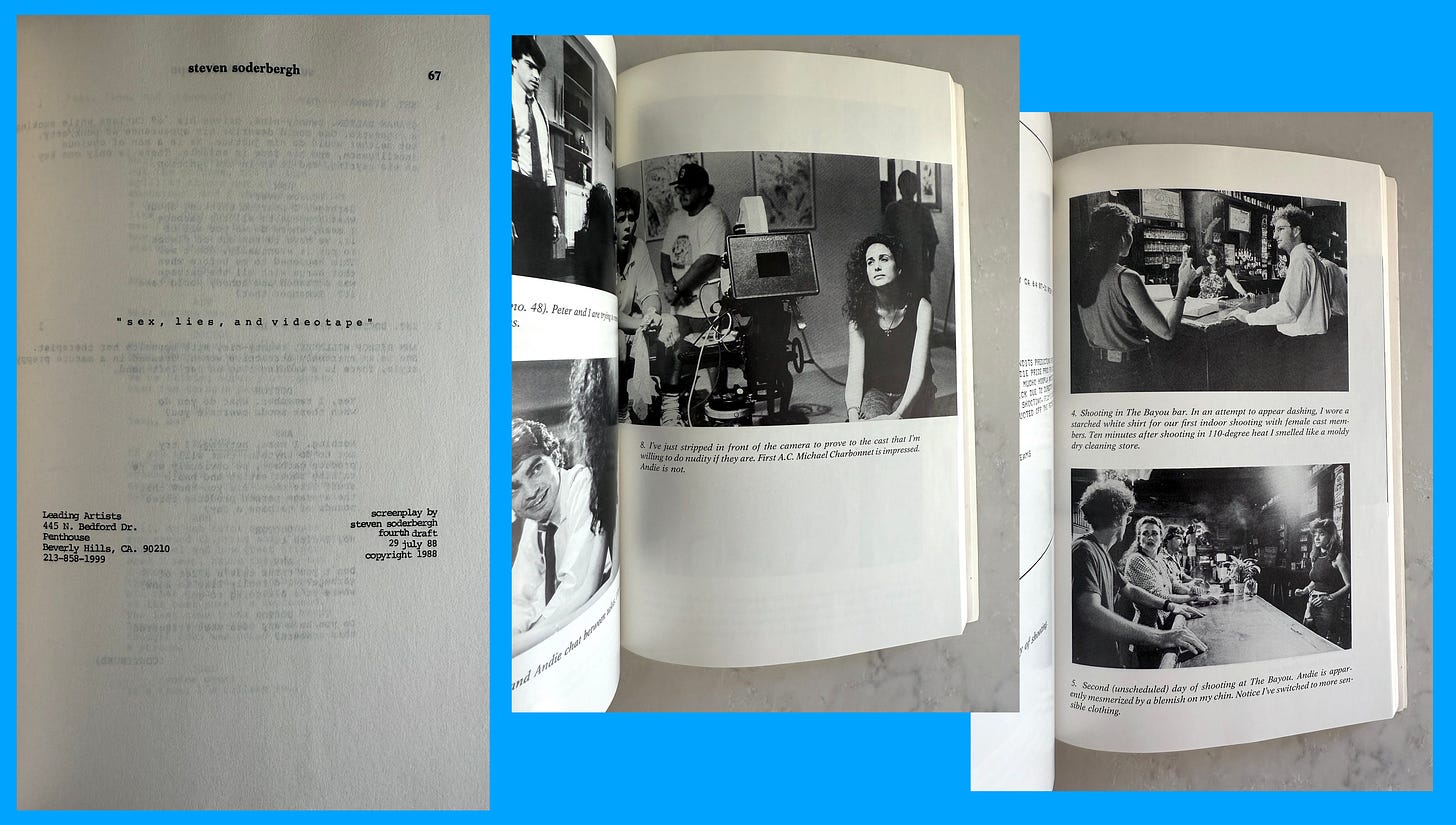

While we’re on the subject, I (Matt) was wandering around the Rose Bowl Flea Market in Pasadena yesterday when I spotted a behind-the-scenes book for another indie film classic… Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies and videotape.

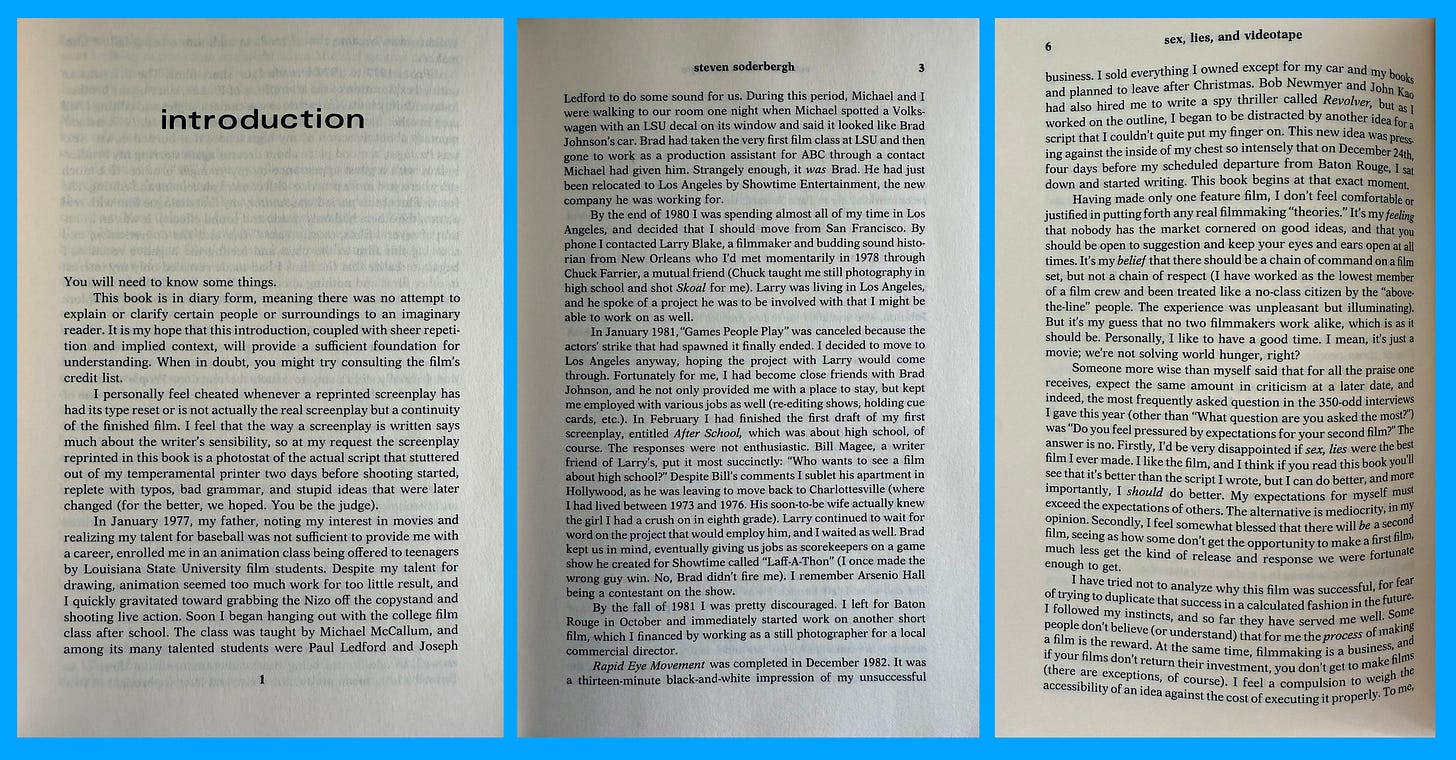

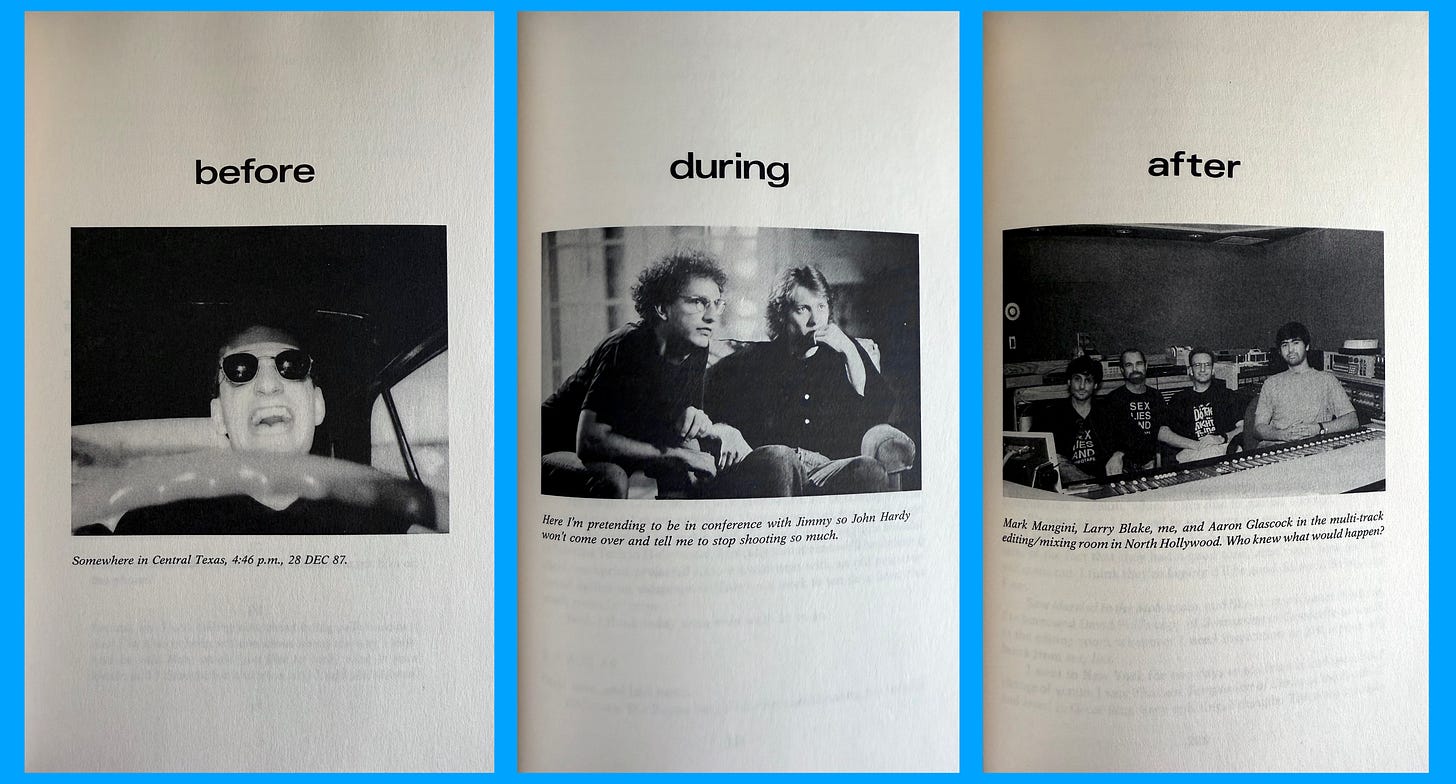

Much like the Slacker book, the cover exudes late 80s/early 90s graphic design excellence and offers readers more of a rare glimpse into the filmmaker’s process than your typical screenplay book. In fact, the actual screenplay doesn’t come until page 67. Instead, the book is essentially a reproduction of Soderbergh’s journal entries from December 1987 through August 1989 and is divided into three sections — BEFORE, DURING and AFTER.

The BEFORE section covers the entire writing process (ending with the properly-formatted, warts-and-all final shooting script), the DURING section covers all of production (with plenty of set photos featuring funny captions written by the maestro himself), while the AFTER section covers post-production, the 1989 Cannes Film Festival, and the film’s release, where it received rapturous, near-universal praise.

But the most interesting thing about the book is that it was published in 1990, at the very beginning of Soderbergh’s illustrious career, so it gives an early glimpse into the mind of a talented young artist who has just experienced his first success after years of grinding it out in the trenches. In his introduction, Soderbergh takes us beat-by-beat through his wilderness years, gratefully name-dropping anyone who offered him a helping hand back when he was just another struggling wannabe filmmaker.

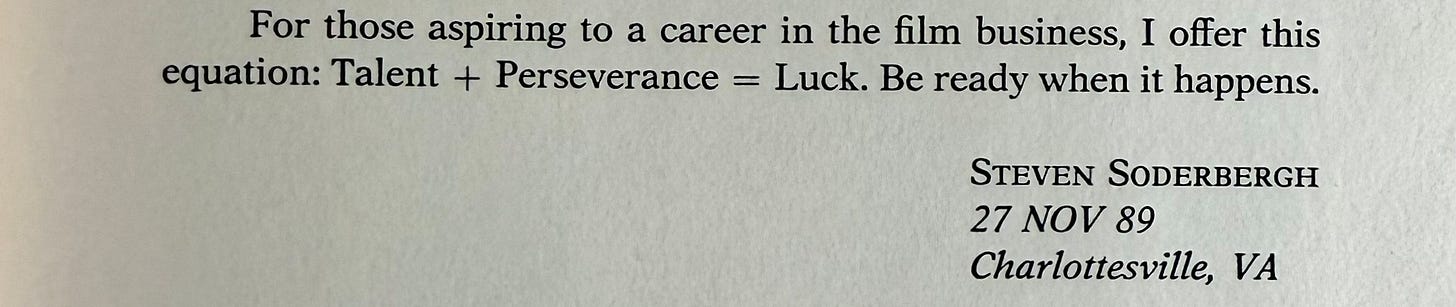

This section ends with an acknowledgment that expectations could not be higher for his next film, but Soderbergh is taking it all in stride. He’s lucky there’s even going to be a second film. But also, luck has nothing to do it. Or as he puts it:

At the time he wrote this, Young Soderbergh (coming this fall on CBS) had no idea he would go on to win multiple Oscars and become one of the most celebrated filmmakers of his generation. He also had no idea that his next five films — Kafka, King of the Hill, The Underneath, Schizopolis and Gray’s Anatomy (no relation to the TV show) — would all be major box-office disappointments from which he would have to claw his way back. This might explain why Soderbergh still continues to grind it out after all this time, having already released one film this year (Presence) and on the eve of releasing yet another (Black Bag). You’d think that after achieving so much the man would need a break, but no. As he says in the intro (and I’m paraphrasing), the work is its own reward, and it can all disappear in an instant, so don’t forget to have a good time while you’re doing it.

“I mean, it’s just a movie; we’re not solving world hunger, right?”

You can purchase a used copy of the book here and the film here.

That’s all for this week. See you next time.

— Dave & Matt