An interview with Alex Ross Perry

We talk to the veteran indie filmmaker (and sometimes actor) about his upcoming documentary, Videoheaven, that he's been working on in secret for the last 11 years.

Alex Ross Perry first got our attention in 2011 with his terrific sophomore film, The Color Wheel. Since then, the man’s output has been nothing short of prolific, releasing a film basically every other year throughout the 2010s. Our admiration of his work deepened even more when he did us the honor of hosting a Q&A of Ingrid Goes West when we premiered in New York. Now, Alex is back with Videoheaven, a documentary about the rise and fall of American video stores, which sounded so Tracking Noise-coded that we decided to reach out to see if he would chat with us. Luckily, Alex is the people’s champ of independent cinema and a major physical media head, so not only was he down to talk, but he also sent us a link to the film so we could watch it in advance. What followed was a fun and wide-ranging conversation about Alex’s filmmaking process, his other 2025 film — Pavements, a fictionalized meta biopic about the (very real) band Pavement — and, of course, all things physical media.

ARP: Thank you guys for watching this movie.

DBS: It was so much fun. It made me want to watch so many movies, because of all the footage you included. There were some I'd never even heard of.

ARP: Such as?

DBS: The Big Hit.

ARP: You’ve never heard of The Big Hit?! Where were you in 1998 when that movie came out?

DBS: (laughs) I don’t know! Is it a good movie?

ARP: It's a really good movie if you like Hong Kong-inspired Hollywood filmmaking. The producer of that movie walked up to us at Rotterdam [Film Festival] after the screening and was like, “I produced The Big Hit, and I spent the first hour of this movie wondering if you were going to have it.” And I was like, yeah, we end an entire section on it. But I'm glad you clocked some movies to watch. Of course that's the hope. You watch something like Los Angeles Plays Itself and it's got 50 of the greatest films ever made in it, and we have 50 of the worst films ever made. (laughter) But I do want people to discover these films, because some of them, to me, are canonical, great films, like Video Violence or The Big Hit, apparently. I highly recommend a lot of these movies, if not all of them.

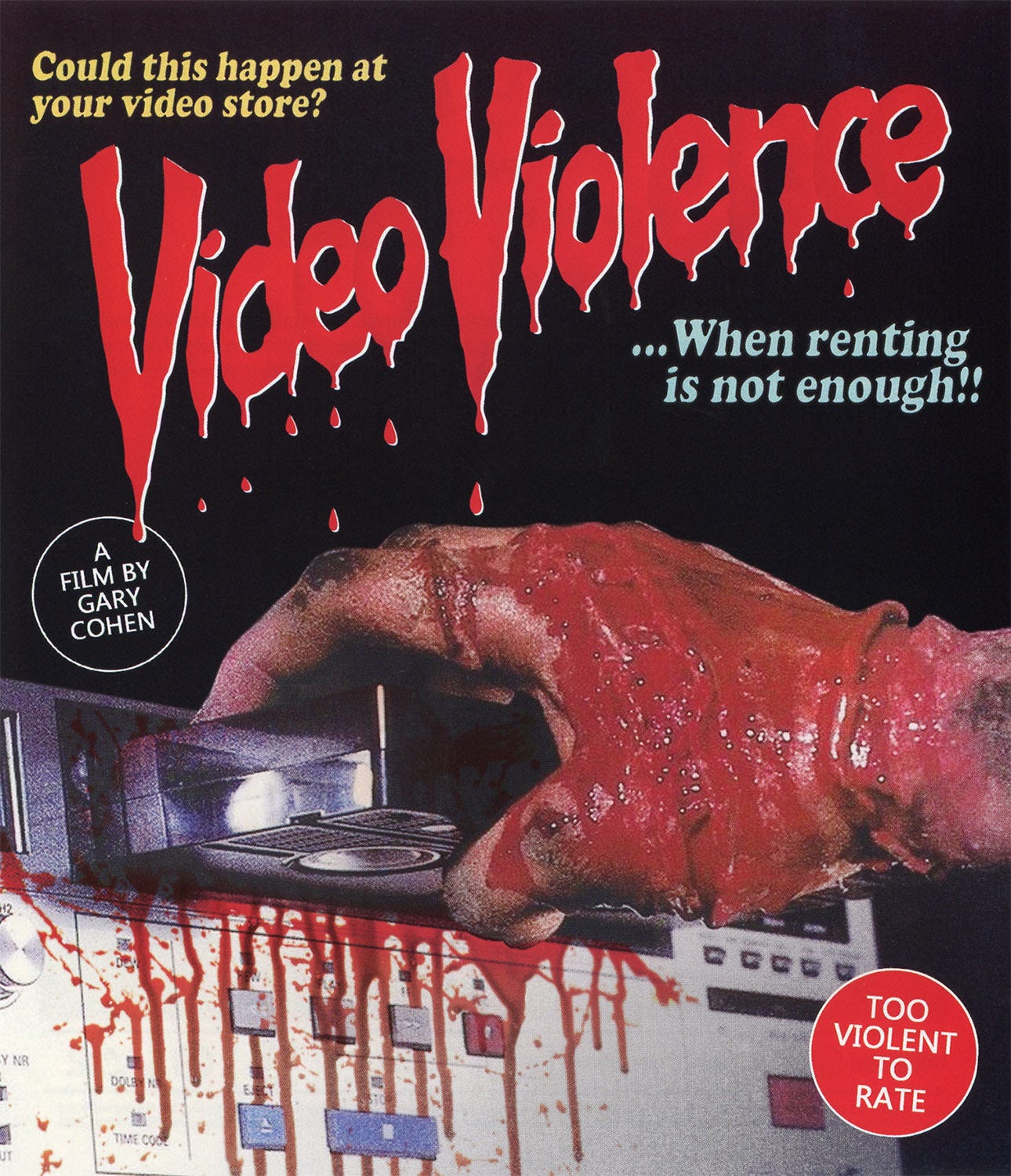

MS: Video Violence was one I'd never heard of because it seemed super low budget. I'm curious how you stumbled upon that one.

ARP: Do you know what the cover looks like? It’s one of those covers that everybody who’s seen it has remembered it for their entire lives. It's a flayed, bloody hand putting a tape into a VCR. Even before you ever saw Video Violence, if you browsed the horror section at the [video] store, that cover jumped out at you. Finally, at some point I watched it, and I was like… this movie has everything. It’s mostly set in a video store, it’s super low budget and charming, it’s set in the Northeast, and when it becomes a horror movie, it's really good and fun. The violence is appealing, the effects are cool, and it instantly became a total favorite [of mine]. I think it's out of print, but Vinegar Syndrome actually did a Video Violence and Video Violence 2 box set.

MS: How big is your physical media collection right now?

ARP: Not very big. I don't really buy that much. Because I worked in a video store for like, three-ish years during the 2000s, back when DVD was really something, I probably brought home a DVD two or three days a week. My purchasing was out of control. Maybe now that I have a house I’ll get back into it, now that I have space. I do buy a lot of [VHS] tapes. Honestly, tapes are a calculable percentage of my annual movie purchasing, because they're just more fun for me. There's this incredibly popular drive-in in the Poconos called the Mahoning, which many [film] nerds and maniacs love, myself included. It's all 35mm programming all summer, April through October, except for one weekend a year when they have VHS Fest. There's like 50 vendors, and they show movies on the big screen on videotape. It's a marketplace by day and then [they’re playing] schlocky fun stuff at night. And it's always right around my birthday, so I always come home with like, a dozen tapes and those are my tapes for the year. Then the next VHS Fest rolls around and my wife and I are there, and I'm like, “You know, we never watched that movie we bought here last year…”

MS: You said in our initial DMs that you've been working on Videoheaven for 11 years now. Can you talk about the inspiration for you wanting to make this and how you went about starting a project of this magnitude?

ARP: I read this book that came out in 2014 by Daniel Herbert that you would love called Videoland: Movie Culture at the American Video Store. It was the first book of its kind to really examine the American video store as a retail establishment. Because I loved the book so much, I wrote him an email and I said, [I’m a] former video clerk [and a] filmmaker and I would love to talk about doing something with your research. And he said, “I cut a chapter from the book about the depictions of video stores on screen, because my editor said I spend half the chapter describing the scenes, and it’s unreadable.” So he sent me the chapter, and I was like… this is the movie. A lot of the key texts in Videoheaven are from that chapter, including some of the really crappy ones. But it got us started. He had his research assistant make a spreadsheet and made her keep digging, like, what have we not found yet? Then I went out there in the spring of 2015 and we basically watched everything together and took notes. And for four years we would just talk – sometimes weekly, sometimes monthly – and I would ask him questions, and our outline kept getting bigger and bigger. Then the pandemic happened, so I had a lot more time to work on it. And during the [2023 WGA and SAG] strike, I was like, “All right, I now work on this movie four days a week.” At that point, Clyde Folley, the editor, and I had been sitting together weekly for about a year and a half, so I was like, let's not just do one night a week from seven to 11. Let me come over on a Monday at 10 AM and let's work all day. And it just kind of went from there. So 11 years sounds like a long time, but two of those years was just me and Dan talking on the phone, saying things like, What points do we want to make? What did you do in your book that we can expand on? And what did you not do in your book? Ultimately, a lot of the final text is my own extrapolations from his research and the work he and I did together.

MS: Earlier you mentioned Los Angeles Plays Itself, which is one of my favorite documentaries. Was that a big influence on this movie?

ARP: The biggest influence. In 2013 or 2014, that movie was finally released for real [on home video] after having been this sacred object for 10 years that was quasi-illegal. It wasn’t illegal but it wasn’t distributable. It would play at nonprofits and film festivals, there'd be a screening of it here and there, and it played at a friend of mine's theater. Thom Anderson [the director] sent her a DVD-R with a return envelope and a stamp on it. But then it's re-emergence as a finished HD object you could buy a Blu-ray of was the other hand shaking this idea out of my head. I was watching bits and pieces of it constantly on my disc [at home]. Creatively, I'm sure you have this instinct all the time. You see something that you like, and you're like, I've never really thought about this before, but something just clicked for me, and I'd like to do something like that. I'm not looking to make academic essay films, but I was obsessed with the syntax of that movie and what it felt like for me as a movie lover to watch Los Angeles Plays Itself and see hundreds of films synthesized into one thesis that has nothing to do with what those movies were about. But by extracting them and laying them front to back, it becomes this other thing. Even while working on this film, I had Los Angeles Plays Itself on in the background countless times, just to hear the voiceover and occasionally steal a glance. Every so often, I'll be watching some movie, and I'm like, “Wait, why do I feel like I've seen this scene like 100 times? Oh, right. This scene is in Los Angeles Plays Itself.” To me, it's just… it's the North Star, and I would say it's my favorite documentary. And if I could make something that deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as [that film], then I feel like I’ve spent my time well.

MS: Well, I think it does. I think it’s really cool to tell the story of video stores using footage of video stores from other films. I saw [Los Angeles Plays Itself] in film school in a photography class, because my teacher was friends with Thom Anderson. She had a bootleg DVD that he had given her so she screened it for us and it blew my mind.

ARP: It’s really incredible. If you've never seen that movie, watching it [for the first time], you're just like… I didn't know you could make a movie that looked like that. I didn't know that something that is just pre-existing images and text could be that riveting.

MS: F For Fake is another one where I was like, I didn’t know that was possible.

ARP: A film I love as well that weirdly was a huge influence on Pavements, this other movie I’ve been supporting lately. But F For Fake is 85 minutes and Los Angeles Plays Itself – much like Videoheaven – is a hair under three hours.

DBS: I'm curious about the writing process. Did you go into Final Draft and actually write out, like, the voiceover to play over this footage?

ARP: The text started off being adapted from Dan's work. I would borrow a sentence or I would take a train of thought that he and I had on the phone. And our “script” is really just a Google Doc shared with me and the editor of the text, Michael Keresky. He’s a film critic and historian who writes for Reverse Shot and has written for Film Comment and things like that. Halfway through, I was like, I don't trust myself to be a great writer grammatically, so we brought in Michael. I’m basically having to do two things at once, because we're constantly rewriting the text based on what we're editing, but what we're editing has to be done in harmony with the text. It's like you're making dinner and dessert at the same time. I need to be working on my batter and my frosting, but I'm also roasting a meatloaf in the oven. Thankfully, Clyde has a day job as an editor for The Criterion Collection so he's always dissecting movie clips and picking them apart for what is needed and he's excellent. That’s why I asked him to do the movie. It’s pretty tedious stuff but it was also a delight because every night we were doing this I was spending time in a video store.

MS: Do you feel like working on this documentary has influenced your narrative work and vice versa? Did it change how you work on narrative stuff?

ARP: The only answer to that I can give that’s concise is, if I started this in 2014, 2015… the three things I’ve done that are major projects for me – Videoheaven, Her Smell, and Pavements – are all largely set in the ‘90s, i.e. during my youth. It’s this fun thing we all do as we get older which is, we kind of just want to run it back. To give ourselves an excuse to live back in a time where we feel like things made more sense. As we say in the film, Body Double was the first Hollywood movie to portray a video store on screen. And that movie came out about four months after I was born, in 1984. So this movie is the story of my lifetime. It's not my life story. But this is the story of 1984 to the present, and specifically as it relates to movie spectatorship and the idea of what it means to watch a movie, told over my lifetime. Everything that happens in this movie happened to me at some point. I was a customer, I was a clerk, I was a shopper. Now I'm a period piece. Now I'm nostalgic for something that's gone.

DBS: Did you ever consider putting more of your personal perspective into the voiceover? I love the lyrical aspect of it, but did you ever think of being like, “In the years I worked at [iconic Manhattan video store] Kim’s Video…” or whatever?

ARP: Because this was largely inspired by Dan's book, I never thought about it that way. The illusion of academic neutrality was really important to me. But I think a close read hopefully shows that the first three parts of the film – the introduction, which is just pure facts about video stores, the second part, which is about the 80s, and the third part, which is about the heyday of the [video] store and its normalization – those parts are all factual. And then the next couple of parts – the porn part, the part about the [video store] clerks, and the decline-and-fall chapter – are subjective. Those are my extrapolations of what this has come to mean in retrospect. A big thesis I arrived at after watching these clips over and over for years was I believe that Hollywood was complicit – whether deliberately or not – in conditioning viewers to think video stores were bad. I'm not saying there was some conspiracy to market the idea of video stores being bad. But the more I looked at this, the more I was like, What happened? And what happened was we had 15 years of… every time you saw someone go to a [video] store [in a movie or TV show], it was negative. Every single time it turned into something bad or stressful. Now that may seem like fun and games, but I think that just made a generation of people go, you know what? I don't wanna go anymore. Who cares? So that's not a fact, that's just my opinion. But the movie kind of hinges on that opinion being taken at face value. And you could show these 160, 70, 80 clips to 10 different people and they'd be like, “That's not my interpretation of what this means at all.” That's just what I [Alex] believe happened to them having worked in [a video store] in the 2000s.

MS: I thought that was one of the most interesting ideas presented by the film – that Hollywood filmmakers and writers are at least partially responsible for the death of the video store because of all these negative portrayals of it. It may have been a reflection of what was organically happening in the culture. But I do think it coincides with Hollywood relinquishing its cultural power. Now if you're trying to cast a movie at a studio, they're like, you need to hire this TikTok star. They're chasing what's popular rather than dictating culture and saying “this is who's cool” and then presenting that to the moviegoing public.

ARP: Yeah, no, that's very much a part of it. The movie industry really sold itself out [and started] chasing trends rather than dictating them. Many billions of dollars were made from [home video] to the point that it was often neck-and-neck or even eclipsing theatrical revenue. So as I say in the movie, it would be in nobody's best interest to make this revenue go away. But of course, that is what happened. And the effects of it are a version of what you're describing, where [the industry] basically cut one of their own legs off, whether accidentally or not. But that's kind of the point of Dan's book, which is that movie culture used to be inextricably linked to American retail culture. In the eighties, you couldn't go 10 miles without finding a video store. And that has changed during our lifetime to being almost nothing. I saw this story recently about how Barnes and Noble is opening triple-digit new retail stores this year, which is great news for everybody. Now nobody lives more than an hour away from a bookstore or a place to buy vinyl [records]. But this one thing [i.e. video stores] went away and was replaced with absolutely nothing. It's so confusing to me, because the music industry still exists. It survived the internet. In our lifetime, we’ve gone from “Napster ruins everything” to “there's a vinyl section with Taylor Swift and Sabrina Carpenter at every Target.” They're now opening new superstores for books. Imagine if Blockbuster was adding a hundred stores this year to keep up with the demand of Blu-ray. Nobody would believe that.

MS: It does feel like we're experiencing a sort of general technology hangover. There was a time when I was completely content to buy or rent everything digitally and I've since re-entered this phase of like, no, it's actually important to me to physically own certain objects, like an album I particularly love. It's important for me to go out and buy it on vinyl or buy the Blu-ray or whatever. We’ve bought into the whole Spotify, streaming thing for 10 years now and we're looking back at what we had and being like, maybe we shouldn't have thrown that away. Maybe that experience was valuable.

ARP: This movie hopefully transports people to three hours of living in that headspace. Yes, it’s a way of enjoying the stories that you want to consume, but it's also a way of training your brain to exist in a certain way. As I show dozens of times in the film, getting to the point where you were on your couch with a video involved a social adventure into a physical space and it required effort. It’s about a time where movie consumption was limited to fixed spaces and fixed quantities. That's a concept that doesn't make any sense to anybody anymore. I know what “sold out” means, but I don't know what it means to be like, this new release just came out and I can't get a copy of it because I got here on Saturday night instead of Friday night. And I think that's really fun. I think I preferred it that way and I still do.

MS: I wanna talk about the ending for a second. Something else that stuck with me was the I Am Legend and Omega Man of it all. This idea that if you were to remake one of those movies, all the scenes of Will Smith in the video store or Charlton Heston at the movie theater wouldn’t make sense anymore. There’s no modern equivalent. At least not one that would survive the apocalypse.

DBS: I thought the ending was really powerful, with Will Smith and the mannequins recreating this social exchange that reminded me of encounters I had with friends or video store clerks. Not only did we lose these physical objects but we lost this really important communal space.

ARP: As we say in the movie, why doesn't [Will Smith] just take every single one of these DVDs home with him? And it’s because what he wants isn't just the ownership of the movie to watch in this world where there's no other people. What he wants is the [human] interaction. That scene is important to me because I used to walk by that [Tower Video] location every single day because when I worked at Kim’s and went to NYU it was like two blocks from there. By the time I Am Legend came out, that store was already gone. It was a shitty store with a terrible selection. It wasn't fun or cool or beautiful or anything, it was just a repository for shit new releases. And yet, 15 years later, I'm happy to spend time just remembering that that was a physical space that used to exist on my daily walk to school.

MS: I had a similar experience watching your film when you play the clip from [Paul Schrader’s] The Canyons –

ARP: I knew you were gonna say that. Amoeba Music.

MS: Exactly. I still go to Amoeba Music all the time and I think the new location is great and I'm so glad it still exists. But there was something about that original location, that building, going up those stairs to the second level where all the videos were that I did feel that pang of nostalgia for it.

ARP: We made sure to leave that clip to play until it pans out over the whole store because we knew people would enjoy seeing that.

MS: What’s the plan for the release of the film? Can you talk about that at all?

ARP: Yeah, I mean, it was made by a non-profit so we own it and we can do anything we want with it, so the plan is that anybody who wants this movie can have it. If you want to screen it at your film school? Great. If you want to screen it in the back of a video store? Great. If you want to screen it at a cinematheque on a double feature with Body Double? Great. The U.S. premiere is coming up in a few months and then we'll start booking it wherever anyone wants it. I just put up the poster on Instagram and already 40 or 50 maniacs were like, “We'll show it!” So I was like, great, email this guy at our non-profit and he'll get it booked. I just want people to see it.

MS: Are you planning to do a physical release?

ARP: Oh, definitely. It's coming soon to two-tape VHS for sure and we’ll do a proper Blu-ray as well. My dream is to only have it on tape for the remainder of this year. It'll be on streaming and Blu-ray next year, but for now you can only take home a two-tape VHS of it. I think that's correct. But we'll do a normal release for sure.

MS: Can you say anything about Pavements? Have you announced a release date yet?

ARP: It opens May 2nd at Film Forum in New York and the following Friday at the Nuart in L.A. And because Film Forum is still a traditional theater and such a coveted booking for documentaries, we have a 10-week exclusive theatrical, so the movie doesn’t hit VOD until July. We’re also finishing up the Vinegar Syndrome / Utopia label Blu-ray which is extravagant and amazing.

DBS: I don't quite understand what the format of it is, but that's what makes it exciting for me.

ARP: The movie or the Blu-ray?

DBS: (laughs) No, the movie. It’s like a biopic musical?

ARP: It’s basically five movies in one. It’s like if you took a band that was important enough to have five movies – like The Beatles or David Bowie or Bob Dylan – and you cut each one down to 20 minutes and edited them all together, that's kind of what the movie is.

MS: Well, we have to ask you because we asked Minghella, but if you could only watch one final movie, what would be your last watch? We presented it to Max like, imagine you’re on death row and it’s sort of like a last meal. You can only watch one last thing.

ARP: Yeah. OK. That’s a morbid “we ask everybody” final question. (laughter) I mean, this is kind of an obnoxious answer because I just did a Blank Check episode on The Elephant Man last year, but I can see that being like a very fitting last movie because it's very beautiful and it depicts voluntary dying as very graceful and humane. But I could imagine watching that being moved emotionally and then watching his tragic but beautiful death and being like, all right, well… (shrugs) …something like that would be very elegant perhaps.

MS: I like that. Not an escapist pick.

DBS: Yeah, you’re almost conditioning yourself for death.

ARP: Well, if the question was like, you’re in I Am Legend and you're about to lose access to movies forever, but you’re going to have to live in a world where you can’t watch them, I would have had a different answer. But you guys have settled on death row, so —

MS: (laughs) OK, now I'm curious. What’s your I Am Legend apocalypse watch?

ARP: Like, I’m going to keep living but this is the last thing I get to watch?

MS: Yes.

ARP: To bring this full circle, maybe it would have to be Los Angeles Plays Itself so it would be like I’m watching 100 movies in one.

DBS: Good answer.

MS: And we’ll leave it at that. Thank you, Alex, for sending us the film and for chatting with us about it. It’s one of my new favorite docs of all time.

ARP: I'm very flattered to be included in the early days of Tracking Noise. Thanks for watching it and taking an extra hour to talk, I appreciate it.

You can follow @alexrossperry on Instagram for more info on Videoheaven screenings at a theater near you, and if you’d like to organize your own screening just shoot him a DM. His other film, Pavements, premieres May 2nd at Film Forum in NYC and May 9th at the Nuart in Los Angeles.

That’s all for now. See you next time.

— Matt & Dave

People used to fall in love at the video store 💔

great interview -- now inspired to finally get around to watching Los Angeles Plays Itself